Dragging AI

In November 2019, Boston Public Library’s (BPL) Teen Central hosted a digital privacy instruction workshop for teens that centered on facial recognition technology. Titled “Drag vs. AI,” the workshop partnered BPL with the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts (ACLU-MA) and Joy “Poet of Code” Buolamwini, artificial intelligence (AI) scholar at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and founder of the Algorithmic Justice League (AJL). BPL and AJL shared the $1,250 program cost.

Last year, I was accepted into the Library Freedom Institute, a train-the-trainer program for librarians who want to educate their libraries and communities about—and advocate for—privacy. Several of our weekly sessions explored the dangers of facial recognition technology, especially its role in automating inequities such as the policing and incarceration of people of color. My final project was to bring this issue to my library union, which supports banning facial recognition technology in Boston and Massachusetts. A comrade and I attended Massachusetts Legislature and Boston City Council hearings on facial recognition, where I testified in support of a ban. In June, the Boston City Council banned the use of facial recognition by city agencies. The state legislature is now considering an omnibus police reform bill that includes a temporary ban on the technology.

I wanted to connect my antisurveillance and privacy work to my Teen Central patrons, many of whom are queer or trans. Public libraries are among the few venues that offer digital privacy training. Making space in the library for teen patrons to explore identity and creatively resist oppressive technology with their own aesthetic was an important goal.

In August 2019, I attended the launch of the ACLU-MA #PressPause campaign in support of the facial recognition ban. As each attendee shared their commitments, I described my plan for a low-budget “horror drag vs. facial recognition” library program for teens that would involve Apple’s Face ID technology. Buolamwini also attended and asked if I needed help. Over the next two months, she, Sasha Costanza-Chock (author and associate professor of civic media at Massachusetts Institute of Technology), and I developed a workshop facilitation guide for a facial recognition program for teens.

Prioritizing digital privacy concerns for teens was a requirement for any technology used in the workshop. The biggest hurdle was finding facial recognition software that wouldn’t funnel participant photos into a database. We couldn’t be sure that wasn’t the case with the facial analysis app we tested, so Buolamwini and her team at AJL built a custom, browser-based tool for the program, which allowed teens to test their drag without compromising their privacy.

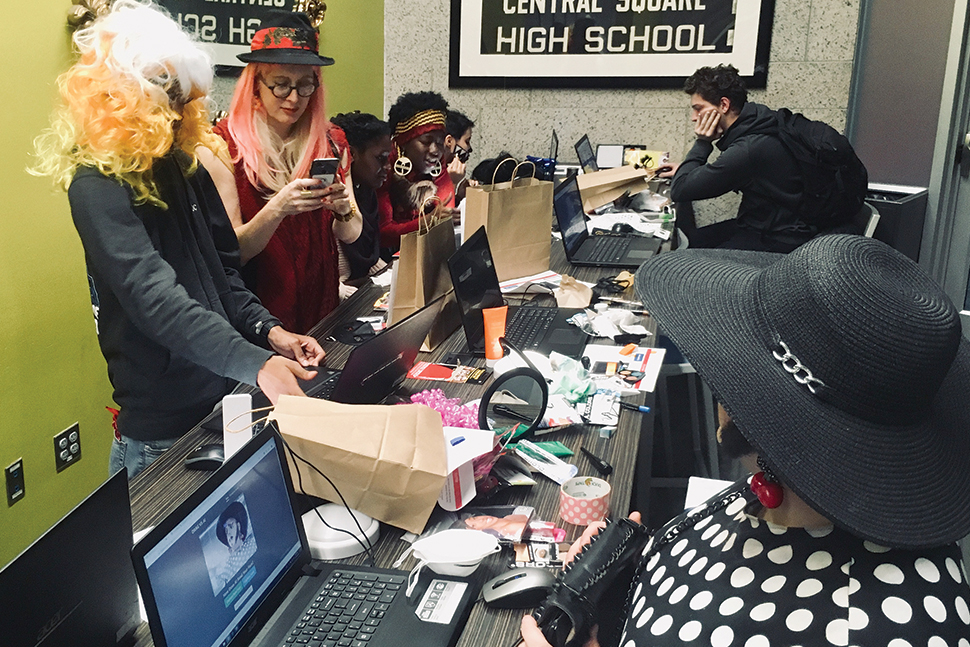

We began the workshop with indigenous land acknowledgments and a screening of Buolamwini’s “AI, Ain’t I a Woman” video. She then broke down the components of facial recognition into “chambers,” with each chamber representing an AI task. Thirteen teens and one Boston Latin Academy instructor worked with Sham Payne, a veteran drag performer, to create looks with makeup and accessories and explore how the algorithms of facial recognition analyze faces to report probability scores based on its tasks. The participants could try to avoid detection in the Ghost Chamber, defy binary gender or age classification in the Drag Chamber and Infinity Chamber, or attempt to lower the confidence score of a match in the Dodge Chamber. It’s important to note that though makeup and accessories have been shown to degrade classification by these systems, as these technologies evolve, both new individual strategies and collective action are necessary to confront this threat to privacy and equality.

Teens could then have their looks photographed. Afterward, ACLU-MA Technology Fellow Lauren Chambers closed the program with a talk about privacy rights and how teens could get involved in the fight against facial recognition. She spoke about individual rights and how efforts to exert community control over policing policies, such as local bans and moratoria on facial recognition, are effective ways to control the spread of invasive surveillance technology.

“Drag vs. AI” was a successful start to a longer partnership to bring this program to teens in other libraries. This experience reinforced that being politically active in a union and outside the library is important, as these new relationships strengthen ties to other activists and experts. Librarians must engage users and colleagues by making space for organizing and advocacy in response to threats to our rights, privacy, and intellectual freedom.

Source of Article