School Librarians Face Reopening Challenges

In Park County, Wyoming, the number of COVID-19 cases is relatively low—only 31 reported as of August 11—and K–12 schools plan to open in-person on August 30. That’s with the understanding that the plans could change at any moment and teaching could shift online.

“Part of our unwritten plan is to spend those first precious weeks when we can be together in person teaching those skills needed to access learning in a remote, virtual environment,” says Jennisen Lucas, district librarian for Park County School District and 2021–2022 American Association of School Librarians (AASL) president-elect. “We hope we will have all year together, but the future holds what it holds.”

In at least 38 California counties that account for roughly 90% of the state’s K–12 students, private and public schools will be entirely remote for the foreseeable future. Two time zones east in New Orleans, classes will be remote until at least after Labor Day, and older students eventually will phase into a hybrid schedule. Down in Banks County, Georgia, in-person classes started on August 7, with high-risk students allowed to opt for remote learning. Masks are mandatory for staff and encouraged (but not mandated) for students.

No nationwide mandates exist for reopening K–12 school libraries this fall, and many schools were still putting together a plan as of August 11. For the dozens of K–12 school librarians who attended an AASL-sponsored virtual town hall on August 5, it seemed like everyone’s reopening plans are a little bit different.

“There are 50 different states with 50 different plans,” says Sylvia Norton, AASL executive director. “Within those states the district has a plan, and within those districts there’s a site-based management plan. What we’re doing is providing resources, so that [school librarians] can speak directly to the decision makers and advocate for their role.”

AASL released its “School Librarian Role in Pandemic Learning Conditions” guidelines in mid-July as a framework for librarians to build their reopening strategies. Most of all, it’s up to school librarians to figure out what works best within their state and district, and to be ready to adapt as the situation evolves daily.

There was a consensus at the town hall that library materials need to be disinfected and quarantined for at least 72 hours after they’ve been returned. That’s in accordance with the Reopening Archives, Libraries, and Museums (REALM) project, a collaboration between OCLC, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, and nonprofit research organization Battelle Memorial Institute. The first phase of the REALM project found that the SARS-CoV-2 virus is not detectable on common library materials after 72 hours.

Still, there is intense debate about how to get books to students. Some school librarians are trying to figure out how socially distanced in-person browsing will work. Many others plan to provide concierge services, in which students browse collections online and the librarians deliver the books to classes or provide curbside pickup for remote students.

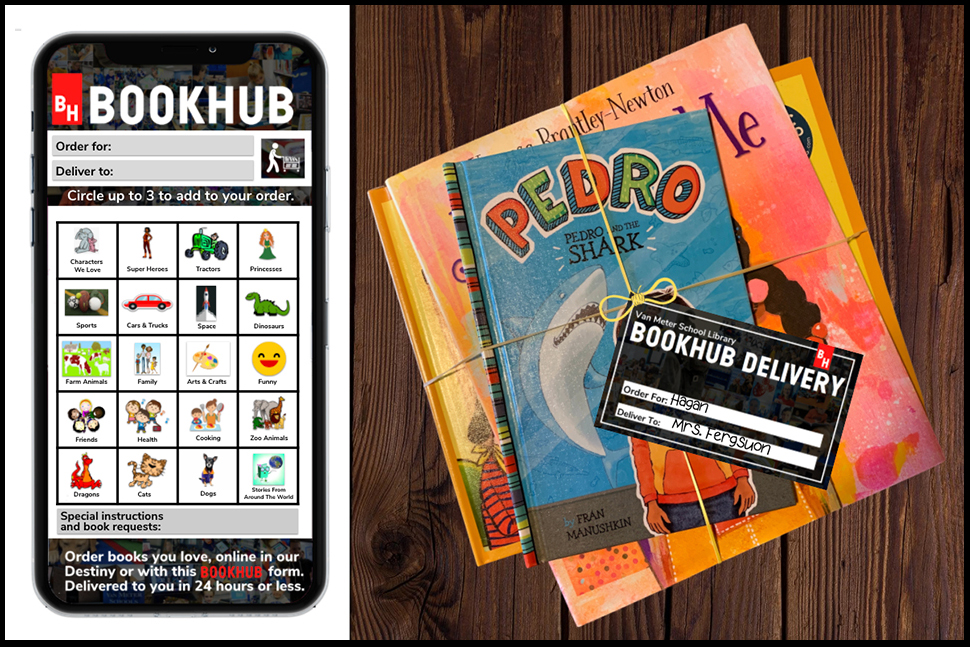

Shannon McClintock Miller, innovation director of instructional technology and library media at Van Meter (Iowa) Community School District, came up with a service called BOOKHUB, modeled after online food-delivery service Grubhub, that allows students to reserve books via the Destiny library management system or by using a printable form. A few librarians even plan to mail books to students.

“We’re using everything but Pony Express,” says Kathy Carroll, 2020–2021 AASL president and lead school librarian at Westwood High School Library Learning Commons in Blythewood, South Carolina. “We can be eager and ambitious because we need books in kids’ hands, but there are set copyright guidelines for how we can share resources. Some of the licensing has been waived by publishing houses, but we have to stay abreast of the current terms.”

Carroll’s school will start virtually in late August on a three-tiered plan. Depending on COVID-19 testing numbers, the district will decide when to progress to the hybrid tier, then face-to-face learning. Her school pivoted to virtual learning in March. She thinks that school librarians are better equipped for the fall after navigating remote instruction in the spring.

“Some school systems have been online for a while, and they’ve purchased databases and had conversations about how to use online resources,” Carroll says. “For other students and educators, it’s been a new world. We heard stories throughout the spring about how librarians assisted other educators to get online.”

In Hempfield School District in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, parents can choose one of four learning pathways for their child to take when schools reopen on August 25: in-person; virtual real-time participation through Google Meet; entirely online through the HAVEN learning program; or a private school, charter school, or home education. Roughly three-quarters of the students chose the in-person option, says Cathi Fuhrman, Hempfield School District high school librarian.

“We need to provide the same welcoming, safe place for students in person and virtually,” Fuhrman says. “The first few weeks will be about checking in with students and their social-emotional learning. School librarians have a myriad of tools to use—books, ebooks, and apps.”

Most Hempfield staff have been told to prepare to teach in-person and online students simultaneously. For librarians, that might mean traveling to classrooms, using a laptop or tablet within the classroom for in-person students, and using a laptop or tablet as a camera to share lessons with students virtually.

“We hope to have time during in-service next week to practice teaching both face-to-face students who are social distanced as well as the students who might be in option two,” Fuhrman says. “When we are coteaching collaboratively with secondary teachers, it will be a great opportunity to help each other. I see the classroom teacher working the camera while we teach information literacy and digital literacy skills to students, and then we as school librarians can then help the teacher by being the camera person for the teacher.”

Source of Article