The Reader’s Road Trip

In 1986, Friends of Libraries USA President Frederick G. Ruffner Jr. had the ambitious idea to start the Literary Landmarks Association, an organization that would encourage the development of historic literary sites across the US. Thirty-five years later, his vision has been realized: 187 Literary Landmarks spanning California to Maine, from childhood homes to writerly salons, public parks to opulent hotels, stately courthouses to seedy watering holes.

“A Literary Landmark is a source of pride for the community,” says Beth Nawalinski, director of United for Libraries, the American Library Association division that now oversees the program. Often the collaboration of Friends groups, community leaders, and literary organizations, these landmarks “demonstrate the power and synergy of those who support the library and literacy at a local level,” she says.

Rocco Staino, chair of the Literary Landmarks Task Force, United for Libraries board member, and director of the Empire State Center for the Book, has personally been involved with 27 Literary Landmark dedication ceremonies (in which plaques are typically unveiled). He believes these sites serve a dual purpose—to celebrate a community’s literary heritage while bringing the people of that place together for a common purpose. “I have attended both small and large dedications, and both have a spirit of excitement,” he says.

For those hitting the open road this summer, American Libraries has curated glimpses of some of these inspiring attractions—many of them outdoors and conducive to social distancing. Read on, mask up, and follow our route to literary greatness.

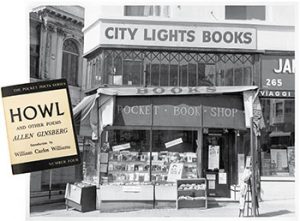

1) Beat Poets of City Lights

San Francisco, California | Dedicated 1992

City Lights was founded in 1953 as an all-paperback bookstore—and later publishing house—by poet and activist Lawrence Ferlinghetti (1919–2021) and sociology professor Peter D. Martin (1923–1988). The shop is credited with democratizing literature and serving as a meeting place for writers and readers of the Beat Movement. After the City Lights imprint published Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems (1956), Ferlinghetti and store manager Shigeyoshi Murao became defendants in a landmark obscenity trial that set First Amendment precedent for controversial work. Bay Area Birthday Party: Since 2019, the city of San Francisco has recognized March 24 as Lawrence Ferlinghetti Day.

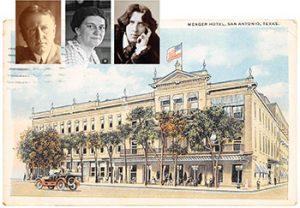

2) Menger Hotel

San Antonio | Dedicated 2000

Established in 1859 only a few steps away from the Alamo, the luxurious Menger Hotel is the oldest continually operating hotel west of the Mississippi River. It has hosted notable guests such as writers O. Henry, Frances Parkinson Keyes, and Oscar Wilde. Adding to the lodging’s lore, President Theodore Roosevelt enlisted his volunteer cavalry Rough Riders in the hotel bar. But the Lobby Doesn’t Look a Day over 112: The building’s marble floor and Renaissance-style details were added in 1909 by British architect Alfred Giles, who greatly influenced San Antonio architecture.

3) Willa Cather Memorial Prairie

Red Cloud, Nebraska | Dedicated 1999

These 600 acres of pristine prairie along US Route 281 evoke the settings of Willa Cather’s (1873–1947) pastoral and feminist novels, including O Pioneers! (1913) and My Ántonia (1918). Red Cloud is home to the author’s foundation and childhood house, where she lived before attending University of Nebraska in Lincoln and working as a journalist and teacher in Pittsburgh and New York City. What Another Literary Landmark Honoree Said about Her: “Miss Cather is Nebraska’s foremost citizen,” once wrote Nobel Prize–winning author Sinclair Lewis (whose boyhood home in Sauk Centre, Minnesota, was dedicated in 2013).

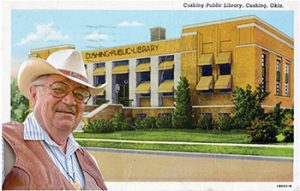

4) Robert J. Conley at Cushing Public Library

Cushing, Oklahoma | Dedicated 2020

A member of the Cherokee Nation, professor and scholar of Native American studies, and author of more than 80 books, Robert J. Conley (1940–2014) is honored with a Literary Landmark in the town where he was born. He is highly regarded for his contributions to Western and Indigenous writing, including novels The Witch of Goingsnake (1988) and Mountain Windsong (1992), often taught in literature classes. How to Be Prolific: Asked by the Appalachian Journal in 2001 if he ever got writers’ block, Conley replied, “No, I don’t believe in it. That would be like having a job in a hardware store and waking up one morning and saying ‘I have hardware store block and can’t go to work.’”

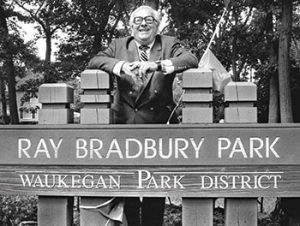

5) Ray Bradbury Park

Waukegan, Illinois | Dedicated 2019

This 1.6-acre plot left an indelible impression on Ray Bradbury (1920–2012), who featured the park—renamed for him in 1990—in Dandelion Wine (1957), Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962), and Farewell Summer (2006). When he wasn’t climbing trees in the park’s ravine, the novelist, essayist, and screenwriter of fantasy, science fiction, mystery, and horror spent his early years at the library. “I got a better education [there] than most people get from universities,” he told Public Libraries Online in 2002. Dramatic Reveal: The dedication ceremony for this Literary Landmark started at 4:51 p.m., in honor of Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury’s famous dystopic work confronting censorship.

6) Benjamin E. Mays Historical Preservation Site

Greenwood, South Carolina | Dedicated 2018

This site features the birth home of Benjamin E. Mays, who was a son of formerly enslaved parents and overcame poverty to become a civil rights leader, Baptist minister, educator, and author. Mays is perhaps best known for serving for three decades as president of Morehouse College, initiating the desegregation of Atlanta Public Schools, and mentoring Black activists, including former students Martin Luther King Jr. and Southern Poverty Law Center cofounder Julian Bond. A Voice in the Struggle: Mays delivered the closing benediction at the 1963 March on Washington as well as the eulogy for King, who once called Mays his “spiritual mentor and intellectual father.”

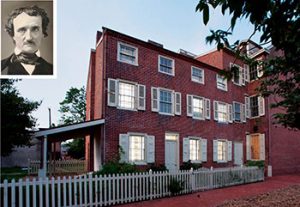

7) Edgar Allan Poe House

Philadelphia | Dedicated 1988

Of the four Philadelphia homes gothic author and poet Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849) lived in, this red-brick house at the corner of 7th and Spring Garden streets is the only one left standing today. It’s here that Poe penned his eeriest stories, including “The Tell-Tale Heart” and “The Black Cat” (both 1843). Guests to the house, maintained by the National Park Service, can tour its stark, unfurnished rooms; it’s likely that Poe sold the furniture to finance his family’s move to New York City. If You’re Heading South: Poe devotees should also stop by the Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum in Baltimore, designated a Literary Landmark in 2020.

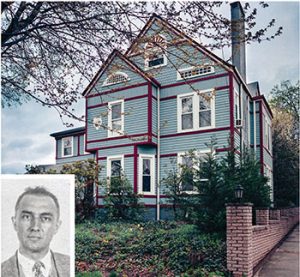

8) William Carlos Williams Home

Rutherford, New Jersey | Dedicated 2005

Though William Carlos Williams (1883–1963) was known as an experimental poet, novelist, essayist, and playwright, this home on 9 Ridge Road where he lived for 50 years is evidence of his—as the Poetry Foundation observes—“remarkably conventional life.” Williams was born and died in Rutherford, and for 40 years he served its residents as a practicing physician. A leading figure of the Imagist and Modernist poetry movements, Williams was inspired by New Jersey’s working class and felt contemporaries Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot were too enamored of European traditions. Green Thumb: Williams was a passionate gardener who tended flowers on the property—and wrote about daisies, primroses, Queen Anne’s lace, and tulips in his poems.

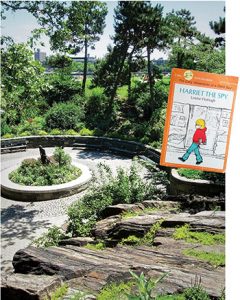

9) Louise Fitzhugh at Carl Schurz Park

New York City | Dedicated 2014

Nestled between the mayor’s mansion and East River on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, this park is regarded by NYC Parks as “one of the city’s best concealed secrets”—though children’s book author Louise Fitzhugh (1928–1974) surely knew about it. In Harriet the Spy (1964), Fitzhugh’s titular protagonist—a brash, 11-year-old aspiring writer who resists gender norms and relishes tomato sandwiches—takes to the park to play tag with classmates, follow Ole Golly on her date with Mr. Waldenstein, and scribble in her notebook. Adults, Watch What You Say: Though Harriet the Spy was controversial when it was published, young readers devoured it—and, according to NPR, started clubs in the 1960s and 1970s to spy on their parents.

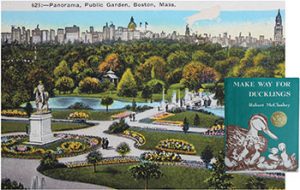

10) Robert McCloskey at Boston Public Garden

Boston | Dedicated 2005

With its pond, recognizable Swan Boats, and bustling foot traffic, Boston Public Garden was the setting for Robert McCloskey’s (1914–2003) picture book Make Way for Ducklings, winner of the 1942 Caldecott Medal. Visitors to this urban oasis—the first botanical garden in the US—can view an earlier duck dedication: bronze sculptures by artist Nancy Schön of the book’s Mrs. Mallard leading her brood down a cobblestone path, gifted to the city in 1987 by Friends of the Boston Public Garden. Illustrious Illustrator: McCloskey was the first person to earn a second Caldecott Medal (in 1958, for Time of Wonder, a story set on Maine’s Penobscot Bay).

Other Rest Stops

Seattle’s Hugo House, the first Literary Landmark in the state of Washington, honors poet and English professor Richard Hugo (1923–1982) and serves as a community center for emerging and established writers.

The Robert Penn Warren Center collection at Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green, honoring the Pulitzer Prize winner (for All the King’s Men in 1946) and former US poet laureate (1986), was a gift of Warren’s family. Included is his personal library, poetry and prose volumes, office furnishings, and awards.

The very first Literary Landmark, dedicated in 1987, was Slip F18 of the Bahia Mar Marina in Fort Lauderdale, Florida—where salvage consultant Travis McGee, a series character of mystery novelist John D. MacDonald, docked his houseboat Busted Flush.

Manila House, a gathering place for Washington, D.C.’s Filipino community from the 1930s to 1950s, was mentioned in Scent of Apples (1979), a short story collection by pioneering Asian-American writer Bienvenido Santos (1911–1996).

Source of Article