Lighting the Way

Poets Reginald Dwayne Betts and Randall Horton both discovered the transformative power of literature while incarcerated, and both have dedicated their lives since their release to bringing that power to others.

Betts founded Freedom Reads, an organization that installs 500-book Freedom Libraries in prisons and juvenile detention centers. Horton cofounded Radical Reversal, a program that creates performance and recording spaces in detention centers and correctional facilities, and conducts workshops that provide creative outlets for incarcerated people.

American Library Association (ALA) Executive Director Tracie D. Hall interviewed Betts and Horton about their work, censorship and access to literature in prisons, and their hopes for ALA’s newly revised Standards for Library Services for the Incarcerated or Detained, which Horton coedited. After the interview, you’ll find a preview of the updated Standards and excerpts from three case studies that appear in the Standards that provide examples of prison library successes.

Tracie D. Hall: Can you talk about the impact of incarceration on your development as writers, readers, and library users?

Randall Horton: I was an average reader at best. However, when I was incarcerated, I had a lot of time on my hands, and my mother actually began to send me books. And that’s kind of where it started: Carl Upchurch’s Convicted in the Womb, Nathan McCall’s Makes Me Wanna Holler. Then I began intersecting writing with that reading. I was in a program in Montgomery County [Maryland] called Jail Addiction Services, and one of the things we had to do was write a letter about our personal feelings, the things we had done to others, and the things that made us operate as human beings.

As I read more, I began to understand what it meant to write. At night, I would dream about passages I read. I could see where the commas and the periods were, and why they used a semicolon and colon—things that I never really understood. That really intrigued me, and that really developed my writing, and I began to explore it creatively.

Reginald Dwayne Betts: I got in and I decided to be a writer because I had this time, and what else could I be? I ended up doing a lot of different things, but saying I would be a writer gave me a locus that I cared about. It’s like the secret that you hold in your heart. But it also will ultimately give me a way to view something that was of value.

The other thing that the arts do is make you feel less like the thing that you don’t want to name. I know I’ve been a few things that I don’t want to tell you about. What the arts do is not necessarily give you a way to not think about it, but they give you a way to remember other things and process the world in different ways. It allows me to see the world as more than what I was seeing before I got into trouble, and to try to shape it into something that matters.

This year, the standards for library services for people who are incarcerated were revised for the first time in 30 years. What kind of access or change in the experience of incarceration are you hoping that these standards can make possible?

Horton: Rethinking the idea of what it means to have access. We live in an ever-evolving digital media, multimedia world in which information shifts states and ways that it is accessible. For someone who uses a book but also uses other information, how do we have access to that within the carceral state? I think the revision is a great steppingstone to get up to speed to what’s going on in today’s society. And hopefully in the next 10 years, it’s revisited again.

Betts: What’s significant about this is the ALA coming back and saying, “We were thinking about this for a long time. And now let us show you how prison is really a bellwether.” We are able to remind ourselves that if you want to know how democracy is failing, then you look at what’s going on in prison.

It’s just a question of what matters. Does who I am matter today more to the country than the crime that I committed in 1996? If who I am today matters more, then the significance of this report is that it’s a step toward the direction where we can have a conversation about the things that got me here and how to get other people to versions of here.

In the 30 years since the last iteration of the standards, we have seen not only the rise of mass or over-incarceration but also the normalization of the privatization of prisons. Privatization has materially shifted priorities away from library services. And literacy as a factor mitigating recidivism became less of a priority. Do you see how these two phenomena are connected?

Betts: The book What Works? [by Robert Martinson] led to the backlash against rehabilitative programs and college courses in prisons and took us to a moment of austerity where we have very little library access and a lot of spaces that don’t have library systems at all.

I would argue that the factors that led to libraries disappearing probably were less about the privatization of prisons and more about the ways in which we decided that prisons are places where we put people who we don’t care about, and we sustain [prisons] by creating more economic opportunities for the companies that provide the infrastructure to keep prisons working.

Horton: You can also look at the Pell Grants and how they were eradicated [for prisoners in a 1994 crime bill; they were reinstated in July 2023]. There’s a correlation there as well because you don’t have as much activity. You see the decline with the way it says what’s more important.

If passed, the Prison Libraries Act—introduced in Congress earlier this year—would grant $60 million over six years to prisons to support library and educational services, with an emphasis on digital literacy for incarcerated people. Do you see any material benefit that might come from this type of legislation?

Horton: It depends on who inside the carceral state takes on that mission. It can be a game changer, but each system within the carceral state is always different. You have to find pockets in which you can make that change, and then hopefully it begins to spread. That initiative is great, but who’s going to get to experience that? I think we haven’t been really cognizant of that.

Betts: In 1997, the year I was locked up, California spent $3.8 billion on incarceration; $60 million for the whole nation is like a drop in the bucket. It’s a start. It’s announcing that we should address this problem, and the only way you address problems is with resources. This is really about valuing the work of librarians. And if the money gets to the librarians, it really will get to people on the ground. But ultimately it’s just a start, and we have to remember that.

In many ways, people who are incarcerated have been experiencing censorship as an everyday, normalized experience. Did you ever experience censorship when you were incarcerated?

Betts: The truth is, I didn’t experience censorship. The first five years, there wasn’t a library. If you have no library, you have no censorship.

I get frustrated by the conversation of censorship. The people who make decisions about books are often undereducated people who haven’t read the book and don’t have time to. When I mailed [my memoir] A Question of Freedom into Virginia prisons, they banned it because I had a chapter called “How to Make a Knife in Prison.” An assistant attorney general in Virginia called us, and I said, “They banned that book because of this line, but I think they’re completely misreading the passage.” We mailed her a copy of the book, and then they were like, “Yeah, it was a mistake,” and they gave all the books back.

Why don’t we hear that story? I don’t want to be upset over the failures because I’m trying to be obsessed over freedom. I want to talk about Freedom Reads and the fact that we put more than 100,000 books in prison.

What’s next for Radical Reversal and Freedom Reads?

Horton: We’re expanding our installations and working with community and educational partners in California, Massachusetts, Florida, and Connecticut. We’re working on a project inside the Suffolk County (Mass.) House of Corrections with Merrimack College [in North Andover]. We’re getting ready to start college credit classes and a pathway to be on campus at Merrimack, where students can continue their education. Our goal is for these expansions to sort of create these senses of creative activity.

Betts: My next phase is how to make anything that I’m doing or Randall is doing or anybody is doing so important that it has a broad national footprint that rivals the footprint that now exists in the public conversation around censorship. Because yes, we need to defeat that. But we defeat it only by getting the public to talk about what really matters, which is all the reasons we went to books in the first place.

Standards Updated

In 2021, a task force headed by ALA’s Office for Diversity, Literacy, and Outreach Services undertook a project to reimagine ALA’s Library Standards for Adult Correctional Institutions. Those standards were originally published in 1992 and are now out of print. The task force included correctional library workers, formerly incarcerated people, and representatives of advocacy organizations.

After two years of hearings, discussions, and feedback, the group is preparing to release Standards for Library Services for the Incarcerated or Detained (SLSID). SLSID replaces both the Library Standards for Adult Correctional Institutions and ALA’s Library Standards for Juvenile Correctional Facilities, which was published in 1999. It expands the scope of the publications, in recognition of the full continuum of incarceration and the inequitable incarceration rates of people of color. It also explicitly addresses incarcerated or detained people’s information needs, with particular attention given to the needs of women, youth, LGBTQIA+ individuals, older adults, people with dementia, people with disabilities and specific accessibility needs, foreign nationals, and individuals whose primary language is not English.

Other revisions in the SLSID edition include:

- The services section has been expanded to include library programs for incarcerated people.

- A new section addresses the assessment of prison library services.

- A new standard addresses censorship in carceral facilities, including policies, appeal processes, and notification requirements.

- Foundational documents, including “Prisoners’ Right to Read: An Interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights,” “Resolution in Opposition to Charging Prisoners to Read,” “Resolution on Library Service to Prisoners,” and “Resolution in Support of Broadband as a Human Right,” have been added as appendices.

- A new section provides professional and networking resources for prison librarians.

- Sixteen “Where It Worked” case studies (see below), contributed by carceral library workers and advocates, provide examples of prison library successes from across the United States and Canada.

- The bibliography has been significantly expanded.

SLSID is one outcome of the Expanding Information Access for Incarcerated People Initiative funded by a Mellon Foundation grant. Thanks to that support, the entire first print run, available February 1, 2024, from ALA Editions, will be distributed free of charge. Request a copy via alastandards@gmail.com.

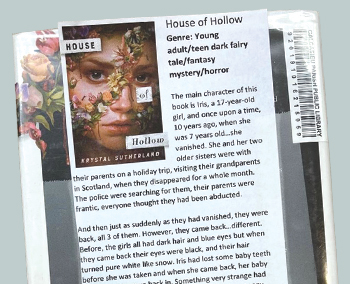

Book Talks for Engagement

A decade-long relationship between Calcasieu Parish (La.) Public Library (CPPL) and the Calcasieu Parish Juvenile Detention Center (CPJDC) has built a thriving partnership that provides reading materials to boys and girls ages 12–17.

CPPL brings discarded or donated children’s and young adult books from all reading levels to CPJDC’s library. Two CPPL staff members also visit the library monthly with a curated selection of 50–70 books, which stay at CPJDC for the month. During visits, staff members perform about 10 book talks. These are informal and often based on the books that young patrons have asked to hear about. CPPL also leaves written copies of book talks with CPJDC staff.

Initially, CPJDC staff allowed CPPL to provide books and book talks only to girls, out of concern that boys would destroy the books. The library recognized this as an equity issue, and eventually persuaded detention center staff to allow CPPL employees to provide book talks for both boys and girls.

The partnership provides library services to an underserved population of young people, and feedback has been positive. CPJDC staffers report seeing some teens reading enthusiastically, while others have picked up books for the first time in years. CPPL staffers have seen the effect their book talks have had on their young patrons; often, the books discussed get checked out immediately.

Adapted from a narrative by Jayme Champagne, outreach librarian at Calcasieu Parish (La.) Public Library.

Making Friends

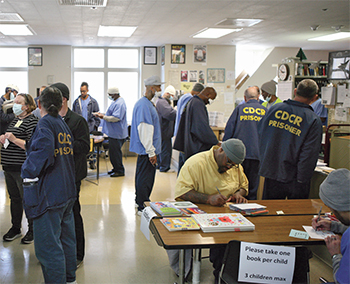

Many public libraries receive financial support from local Friends groups. The Friends of the San Quentin (Calif.) Prison Library, run by library workers who are incarcerated and outside volunteers, provides a similar service to the San Quentin State Prison library.

The organization raises money to add materials to the library’s collection. San Quentin librarians also maintain wish lists at a local bookstore and on Amazon to accept donations based on patron requests and educational and legal needs.

Another program the Friends group carried out was the San Quentin Book Fair for Incarcerated Parents. After receiving a donation of new children’s books before the holidays, people incarcerated at San Quentin were allowed to select books to send to the children in their lives. The book fair was largely run by the library’s 14 incarcerated staff members.

The Friends group has in-person monthly meetings and occasional phone meetings. Despite this, communication is a challenge. Incarcerated library staffers are heavily involved in the group’s work, but they are not allowed to participate in group emails. It can also be a challenge to engage would-be outside volunteers, as the group does not operate book sales like many Friends groups do.

Nevertheless, the group has ambitious goals, including expanding the book fair and adding a summer reading program–themed fair, providing library courses and technology help to incarcerated library staffers, and collaborating with public libraries to offer interlibrary loan, reference services, and reentry support after release.

Adapted from a narrative by Kristi Kenney, Friends of the San Quentin Prison Library cofounder; Gabriel Loiederman, San Quentin senior librarian; and Aaron Dahlstedt, San Quentin librarian.

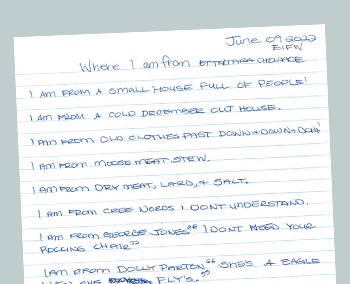

Art as Activation

Every two weeks, participants in the Edmonton (Alberta) Institution for Women’s (EIW) Correspondence Book Club receive a package of books, art, and writing and art prompts. Materials are selected by staff from University of Alberta (UA) Library in Edmonton, as well as the university’s Humanities 101 lifelong learning program and its Indigenous Prison Arts and Education Project.

Half of women incarcerated in Canada are Indigenous. The books and artwork selected for the program therefore prioritize work by and about Indigenous people. In particular, the readings depict Indigenous people thriving, resisting colonial structures, reclaiming culture and language, and living joyfully. Also included are readings that correct common misconceptions about Indigenous sciences, laws, and histories.

The book club packages’ themed writing and art-making prompts encourage participants to engage with the materials. One participant collaborated with her children over the phone to create and describe new superheroes and their worlds. Another shared writings and illustrations based on her experiences growing up in the bush with her Nêhiyaw (Cree) family. Participants were invited to include their work in a magazine distributed at EIW.

Program participation is high; 123 women took part during the 2022 calendar year. During weekly office hours for each of the three security levels, up to 15 women would attend and discuss the readings and artworks, and several women who were soon to be released asked if they could continue to receive the packages in the mail.

Adapted from a narrative by Allison Sivak, librarian at University of Alberta; Lisa Prins, UA Humanities 101 coordinator; Jessica Thorlakson, UA librarian; and Sarah Auger, project coordinator, Indigenous Prison Arts and Education Project.

Source of Article