Collecting Coronavirus Stories

The Palos Verdes Library District (PVLD) coronavirus archiving project started with a cat.

Monique Sugimoto, archivist and local history librarian at Peninsula Center Library, a branch of PVLD in Rolling Hills Estates, California, was quarantined at home in March like the rest of her staff and patrons when she sent a photo of her feline home office companion to her team and asked them to share their own remote workspaces. The responses, which included an image of a colleague’s dog refusing to relinquish a work chair, made Sugimoto realize she could prompt the whole community to capture a snapshot of life in the time of coronavirus.

“I realized how upside-down our world had changed,” she says. She sent a request through the library’s channels inviting the library community to share their COVID-19 stories and images, saying, “Your contributions will help build a resource of primary documentation so future generations can understand the history we are now living.”

Sugimoto’s library is one of many asking its community members to contribute to local coronavirus archives. Some, like PVLD, were inspired by the way their community had been affected by prior global events. In 2016, Sugimoto began gathering history and records from the area’s aging population—many of whom had lived through World War II—for a collection called Your Story Is the Peninsula’s Story (YSPS), which shares a home in PVLD’s digital repository with the Coronavirus Pandemic 2020 Collection. “We have all these seniors who are aging and passing away.

They’re taking all their knowledge with them; the history they have of the [Palos Verdes] Peninsula is evaporating with them,” she says. In a letter translated into Chinese, Farsi, Japanese, and Korean, she asked community members to bring in any documentations of change within the area over the decades since developers arrived in the 1920s.

Lisa Cohn, special collections librarian at Bloomfield (N.J.) Public Library (BPL), says that the World War II section of its collection includes well-kept records of the contributions community members made to support the military overseas. “It looked like a librarian had put out a call for people to say what their organizations did to help the war effort,” Cohn says. She thought, “let’s do the same thing to collect COVID-19 stories.”

Soliciting history

BPL’s COVID-19 Archive Project invites patrons to share documents, handwritten journals, social media handles, photographs, audio/video recordings, drawings, and poetry. In some cases, the call for documents has opened a discussion of what counts as history.

“It’s a tricky thing, because a lot of people don’t think their knowledge or experiences or history are important,” says Sugimoto. “It’s not just the history textbooks. It’s their interactions that build the community. The idea of what is historical is not that well understood.”

Mark Shelstad, coordinator of digital and archive services at Colorado State University (CSU) Libraries in Fort Collins, wanted to capture the campus experience broadly by launching a project encouraging students, staff, and faculty to document their personal experiences during the coronavirus outbreak and contribute them to the university archives.

Shelstad started by documenting the real-time changes reflected in university communications. “Obviously first was capturing the university’s website and all these changes and updates that came about before spring break,” he says. “Then we wanted to see if we could get individual contributions from the campus community.”

He asked students to write about what it was like to miss spring break, go home, have to quit a job, or move in with parents. “We were also interested in how this affected them personally in terms of finances as well as studying in online courses for the semester.” One of his favorite submissions came from a student photographer who documented another student working as a nurse, capturing the time and precautions she had to take to avoid getting coronavirus.

Marietta Carr, librarian at Grems-Doolittle Library and Archives, part of the Schenectady County (N.Y.) Historical Society, included prompts for its COVID-19 collection project: Who did you talk to today? What did you talk about? How did you feel during and after the conversation? What new piece of information did you learn today? How do you think you will use this information? Where did this information come from? Why do you trust the source of this information?

Carr says sites like History Colorado and A Journal of the Plague Year gave her “ideas for specific questions that might prompt answers rather than just a ‘Hey, we’re collecting!’” Like Sugimoto, she encountered patrons who didn’t think their lives were interesting enough to merit a journal. “One of the things I suggested when people talked to me about those concerns was, ‘Are you talking to your family more often? Could you keep a record of what kind of conversations you’re having? You might feel like you’re not doing much and not anything worth recording, but those conversations can be valuable information,’” Carr says. Thanks to widespread electronic communication, she says, there’s little physical record of our everyday lives unless people make a point of collecting and sharing it.

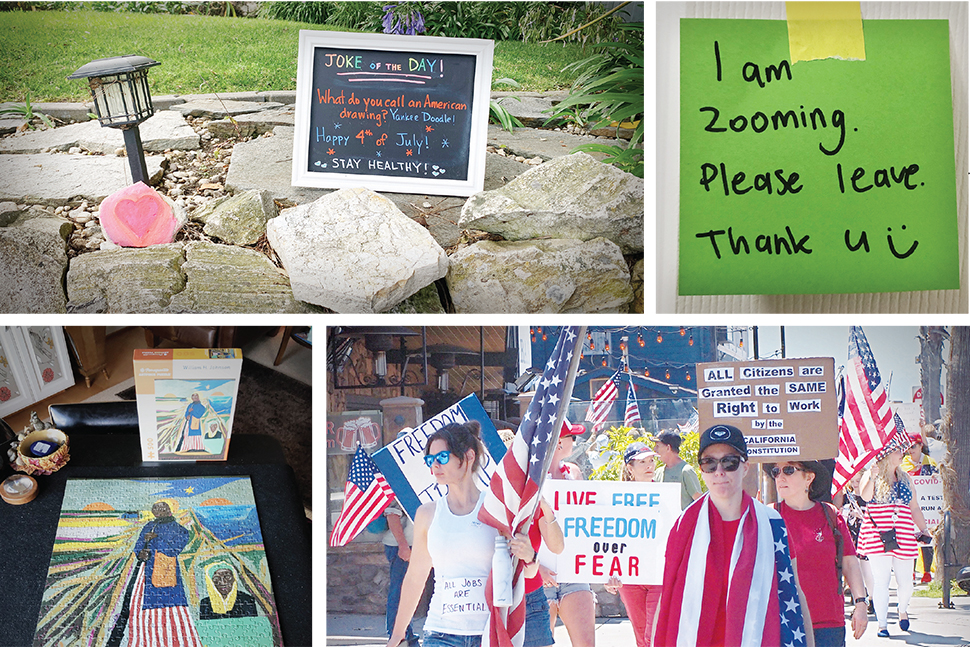

As of early October, Sugimoto had received 106 submissions—some even from out of town—that included photos of plastic dividers at the grocery store, restaurants promoting their takeout services, and a sign on a tween’s bedroom door saying i am zooming. please leave. Some sent photos of peaceful streets. “Here in Southern California, no traffic on the freeways is an incredible sight in itself,” says Sugimoto.

Carr says she received COVID-19 haikus written and submitted by a local writer’s group and a report from members of a local quilting group who made and distributed masks, along with some samples of their project. “That was interesting because it was not something we had specifically asked for or expected,” she says. “It was also amazing how organized and detailed this group was when they went into production and how organized they were with their recordkeeping.”

Along with figuring out how to elicit contributions, many librarians building COVID- 19 archives have strategized how to be truly inclusive in their collections. BPL, for instance, has many immigrant patrons, and Cohn says that she asked one of the library’s ESL teachers to consider using the new archive as a literacy lesson: “I wanted to know what it’s like for people who just came here—maybe they’re really cut off from their family.”

Carr observes that most responses she’s received so far have come from retired older white people who may have extra time to record and submit and are not representative of essential workers, the African-American community, the Latinx community, or recent immigrants. “Those are definitely populations that we want to work with specifically to document their experiences. Especially right now, with Black Lives Matter and the other recent protests. We want to be mindful of that and supportive of that,” she says, “rather than just be passive about it.” Carr is contemplating expanding her library’s project to include oral history and photography that captures the lives of health care workers, small business owners, and unsheltered members of the community. As she says, “If you don’t have access to a computer, how can you send me your emails?”

Systems and tools

Each library’s system for submission and storage varies according to their existing resources and systems. Shelstad admits that Google Forms might have been easier to use than the current Microsoft form, which requires a university login. But, he says, “we didn’t want to open ourselves to spamming, and it ensured that faculty, staff, and students would be submitting content. It’s a double-edged sword.”

Sugimoto honed her library’s acquisition process with the launch of YSPS, when she took inspiration from projects like University of Boston’s Mass. Memories Road Show. “They have a little handbook about how to conduct these things.” She crafted intake forms to record permissions as well as the formats, contributors, origins, and historical relevance of images and documents. For the pandemic, she moved intake to Google Forms, which can present a hitch for those without a Gmail account, but Sugimoto offers assistance as needed. After a patron uploads an image, Sugimoto adds metadata and uploads the file to the digital repository, a process that takes less than 15 minutes. The files are hosted through Lyrasis, which also handles web security. An additional downside of self-upload versus scanning in person is that Sugimoto can’t always control image quality, but something is better than nothing, she says: “That was one thing as an archivist I had to let go of and say, ‘You know what, this is documenting it. It might not be the highest quality, but it’s speaking to what’s happening now.’”

There are also legal issues to consider, such as permission to use imagery, electronic signatures, and age requirements to ensure minors aren’t submitting without their parents’ permission. Many libraries, like CSU, already have boilerplate language that applies to the request for archive donations. “We have a standard form that turns over certain rights,” says Shelstad. “The donor can retain or pass along those rights to us, and we have the ability to share that content.”

Other challenges and unknowns can be handled only in real time as librarians and patrons alike live through history. It may be difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of calls to contribute as the pandemic stretches on. Additionally, motivating a population that may simply have a hard time taking on new projects can be tough. “The timing is very difficult to work with,” says Carr. “People need to focus on survival first and then take time to reflect. You want to capture the moment as it’s happening but not detract from anyone’s energy that they’re putting into survival or easing suffering.”

Resources

The librarians in this story used these online collections and resources when strategizing rollout, engagement, technology, and legal issues:

The Blackivists. A group of Black archivists in Chicago trains and consults with community groups on how to properly preserve archives, prioritizing projects that fill in the gaps in history.

Documenting the Now. A tool for and community dedicated to ethically capturing social media content.

The Tenement Museum. Sugimoto used its call for stories and submission form when putting together the updated YSPS request for submissions.

Society of American Archivists. Its Documenting in Times of Crisis resource kit provides templates and documents that assist archivists in collecting materials on tragedies within their communities, including toolkits for collecting oral histories, resources and ethical considerations when working with trauma-based collections, and practical digital content guides.

Source of Article