Chronicling the Black Experience

In September 2018, Rodney E. Freeman Jr. was at home lying on his couch when he heard about Botham Jean. Jean, a 26-year-old Black accountant in Dallas, had been shot and killed by his neighbor, a white Dallas police officer, when she entered his apartment thinking it was her own. The incident compelled Freeman to consider how Black men are perceived in the US.

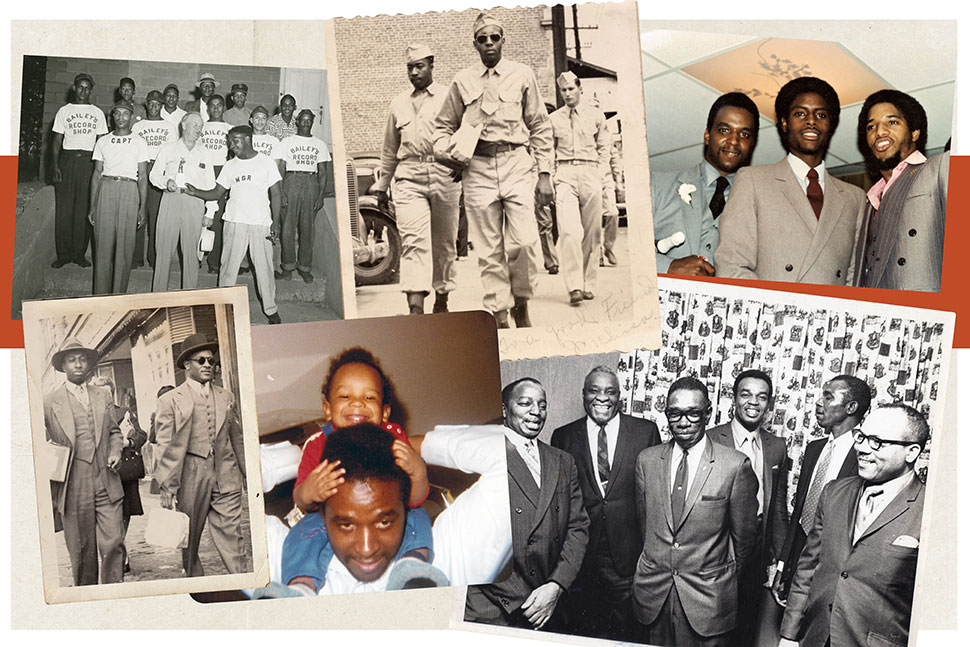

“I felt there weren’t enough stories portraying positive Black men,” says Freeman, director of Riviera Beach (Fla.) Public Library. “If people, mainly white people, saw us in a more holistic light, as fathers, husbands, and leaders, they wouldn’t automatically assume we are criminals, monsters, and demons.”

To fill this need, Freeman created the Black Male Archives, an online repository to “capture, curate, and promote positive stories about Black men around the world while inspiring and informing younger generations,” according to its website.

Freeman is one of a number of archivists who have chosen to create their own archives around the Black experience in America rather than participate in an institutional archive, such as those maintained by universities or other large library systems. These archivists cite a variety of concerns about institutional archives, including gaps in what information is included, inconsistency in documenting Black history and events, and not enough community-level content.

Archiving without barriers

Prior to joining Riviera Beach Public Library, Freeman managed the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature at Woodson Regional Library in Chicago. He also helped assemble a digital archive for the African American History Committee at Indianapolis Public Library and archived and digitized the history of Bethel A.M.E. Church in Indianapolis. This experience prepared Freeman to create his own archive to fill what he says is a glaring void.

“I didn’t find anything in archives that focuses solely on the Black male experience,” Freeman says. The Black Male Archives responds to this gap by collecting articles, photos, podcasts, and YouTube videos specifically detailing the experiences of Black men in the US.

“We’re more of an aggregator,” Freeman says. “There is some content we create, but for the most part we try to amplify what’s already out there.” A sampling includes photos of Black fraternities in America, a map of Negro National League (1920–1931) baseball teams, and information about Black entrepreneurs and Black male writers.

This same desire to curate stories not being told elsewhere is what compelled six Black archivists in Chicago to create the Blackivists in 2018. The group provides professional expertise on cultural heritage archiving and preservation practices as they apply to historically underdocumented communities. The group specializes in collection development and care, oral history development, establishing archival collections, community engagement, and digital collections sustainability, with an eye toward the Black experience. They also pay attention to other marginalized communities, including “LGBTQ people [and] folks who are sex workers or criminalized for the work they do,” says Erin Glasco, an independent archivist who works with the Blackivists. “We have a pretty broad and radical scope.”

The Blackivists have worked on projects that include the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials Oral History website, the Oscar Brown Jr. Archive Project, and the Chicago Black Social Change Culture Map (with Afro-diasporic feminist collaborative Honey Pot Performance). They also archived the history of the Black Panther Party of Illinois, interviewing former party members. “For a long time that history was very tainted and inaccurate,” says Raquel Flores-Clemons, a Blackivists founder and director of university archives, records management, and special collections at Chicago State University. “What people knew about the Black Panther Party was a negative history gotten from the police and FBI.”

The Blackivists aim to document marginalized histories but keep those histories in the community. “There are barriers between established institutions and the community,” says Flores-Clemons. A university, for example, might push people out of their neighborhood to expand—and then want to preserve the history of the people it pushed out, Glasco says.

And while archiving always involves selection, Flores-Clemons suggests the selection criteria may sometimes serve the institution more than they serve a fair telling of the history.

“There can be a colonialist mentality in creating archives,” she says. “Items might get into institutions and never see the light of day. Or the collection exists but the unsavory part of the story never gets told. There are collections in many institutions in the Chicago area about somebody of note, and maybe the family doesn’t want part of the story to be told.”

Glasco agrees: “Institutions often play into ‘respectability politics.’ They don’t want to tell certain stories.”

Respectability politics particularly tends to arise from dynamics of gender and class, Glasco says. Archives of the civil rights movement, for example, mostly focus on heterosexual Black men, but other marginalized communities were also vital to the cause and their stories must be told, too. “I’m not saying those collections are not important to keep,” Glasco says, but it should also be recognized that the movement included queer and gender-fluid people, for instance.

“Bayard Rustin, the architect of the 1963 March on Washington, was an openly gay man,” Flores-Clemons says. “Black trans women and Latinx trans women threw the first bottles at the Stonewall riot, and they only got highlighted in recent years.”

There is a slight trend toward improvement among institutions, Flores-Clemons says. Some want to “look into the organization and see where there were missteps and where white supremacy lives,” Flores-Clemons says. “Are they going to direct money from their budget to really do this work so it can be sustainable?”

Creating joy

Glasco thinks the stories of Black people are getting more attention since the uprisings of summer 2020, but wonders why those stories—Black Lives Matter, health disparities for people of color, police violence against Black people—were largely not being collected before 2020.

Makiba Foster, regional manager of the African American Research Library and Cultural Center at Broward County (Fla.) Library, shares this thought. With archivist and scholar Bergis Jules, she formed Archiving the Black Web, a project that aims to organize efforts to collect and contextualize social media and other internet content that focuses on the Black experience.

Foster describes the unique ways in which Black people use the internet: “Creating joy from pain,” she says. “And from pain, figuring out ways of celebration.” She adds that “social media has allowed us to memorialize lives when normal structures and systems deny us that kind of formal recognition and acknowledgement,” citing the online remembrances of Trayvon Martin and Breonna Taylor as examples. More broadly, social media helps communities chronicle “the fatigue of being Black in America.”

“Archiving this is important for future research,” Foster says. “Our project is to evaluate the landscape and create some kind of infrastructure to move forward. There is so much content.”

Prior to her work at Broward County Library, Foster worked at New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. There she created collections focused on content related to Harlem, including materials on businesses and organizations in the neighborhood. Before that, while at Washington University in St. Louis, Foster led a team documenting the protest movement in Ferguson, Missouri, after Michael Brown was fatally shot by a white police officer in August 2014.

Like the Blackivists, Foster sees a problem in leaving archiving exclusively to well-funded universities and institutions, which do not focus on those who aren’t “white and moneyed.” She says that race and socioeconomic factors come into play when those institutions decide whose stories to collect. “We are trying to create space for Black content creators to be part of a digital archive,” Foster says.

Passion projects

The archivists, curators, and librarians collecting Black stories have encountered shared challenges doing their work: There are more stories than archivists to collect them. Building an archive and sustaining it can be expensive. People often don’t see themselves as important enough to document.

“[The Blackivists] is a passion project for the most part,” Flores-Clemons says. “We’re not making gobs of money.”

The Black Male Archives is essentially a one-person operation, and Freeman says he spends at least $500 a month maintaining its website and security certificate. He uses his weekends and weeknights searching for content and promoting the archive on social media.

His work is paying off. The archive’s podcast, which features Freeman telling the stories of Black men from across the world, attracts listeners from as far away as France, Jamaica, Kenya, Lesotho, and South Africa. The archive is also finding use as a teaching tool: Freeman reports that a former librarian friend who is now an educator uses the Black Male Archives in his classroom; a doctoral student at University of California, Berkeley, is incorporating some of the stories from the archive into his dissertation; and in summer 2019, the Black Male Archives was selected for inclusion in the Library of Congress’s Web Archive.

Archiving the Black Web received a $150,000 grant in 2020 from the Institute of Museum and Library Services’ Laura Bush 21st Century Librarian Program to help facilitate its work, and has partnered with several entities including the Schomburg Center, the African American Museum and Library at Oakland in California, and the Spelman College Archives and Auburn Avenue Research Library in Atlanta. Archiving the Black Web also held a national forum in April that focused on strategies for collecting and preserving Black history and culture online as well as developing a community of practice for Black cultural memory organizations and practitioners interested in web archiving.

There is an urgency to archiving the Black experience, says Foster. “The average lifespan of something online is 90 days,” she explains. It can disappear, for example, “if someone didn’t pay a domain fee or declined to upgrade their web page.”

The ephemeral nature of this content makes capturing it both difficult and important. And ensuring it is documented correctly is crucial.

“I don’t want to see stories bastardized and diluted,” Glasco says. “I want to see ourselves in the historical record—not as an afterthought.”

Source of Article