Getting There Together

Coalition, alliance, task force, committee, collaborative. The digital equity coalition is a model that goes by many names, but ultimately these groups share one familiar goal: closing the digital divide. In the years since American Libraries first reported on this trend, these organizations have grown in frequency and scale across the country, with public-private partnerships often setting the agenda for digital inclusion in their cities, regions, and school and university networks.

“During the pandemic, the number of place-based digital inclusion coalitions has more than tripled,” says Angela Siefer, director of the nonprofit National Digital Inclusion Alliance (NDIA), a community of digital inclusion practitioners and policymakers. “The sudden awareness of digital inequities and the need for coordinated solutions caused folks to come together, [and] libraries are often the trusted community entities that are leading coalitions, connecting partners, and gathering resources to increase digital equity.”

We talked with three library professionals about how digital equity coalitions have helped them improve capacity and resource-sharing and supported their communities during the pandemic:

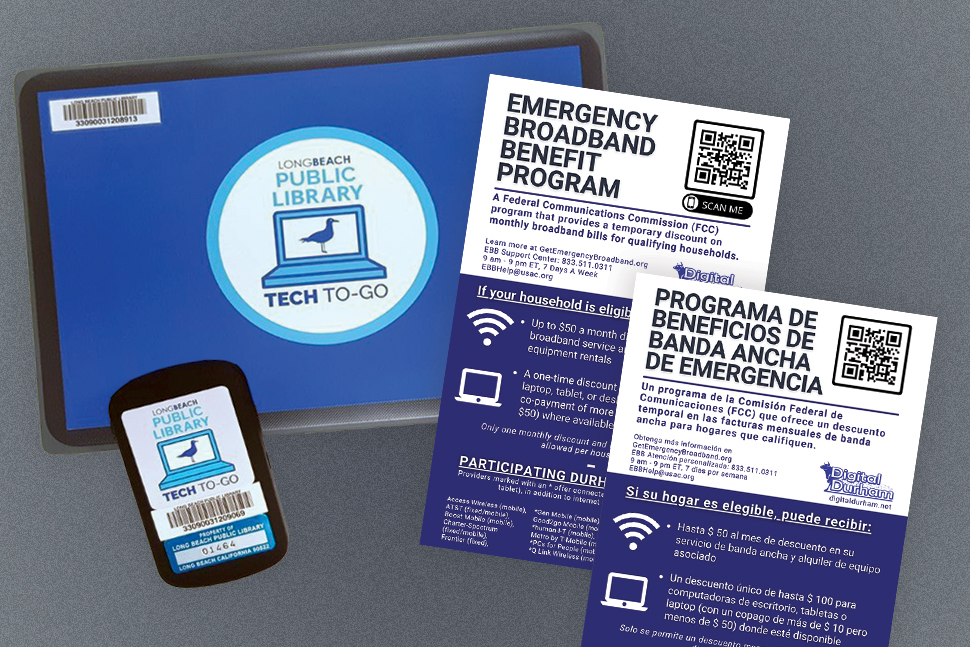

Christine Hertzel, interim director of library services at Long Beach (Calif.) Public Library and Long Beach Digital Inclusion Stakeholder Committee member

Katie Kehoe, grants and communications librarian at F. D. Bluford Library at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro and member of Digital Durham’s grants committee

Dawn Kight, dean of libraries at Southern University and A&M College in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and member of the Louisiana Board of Regents Digital Inclusion Task Force

What digital equity problems does your community want to solve? How did you get involved with a coalition, and who are your local partners?

Kehoe: In Durham County, North Carolina, an estimated 7% of households do not have a computer at home and 13% of households are not subscribed to broadband internet. Digital Durham was founded in 2016 by Jenny Levine of Durham County Library, Lori Special of State Library of North Carolina, and Laura B. Fogle of Durham Public Schools to serve these households.

Our collaborative of more than a dozen members includes libraries and schools, literacy nonprofit Book Harvest, Durham Housing Authority, and Triangle Ecycling, a business that collects, refurbishes, and recycles computers and other electronics. Our group created a formal governance structure in 2019, which has allowed it to apply for a BAND-NC grant and fund the creation of a digital equity plan for the city and county.

Kight: My library supports students who attend Southern University and A&M College, the largest historically Black college and university in Louisiana. Our main goal is to provide access to resources that support learning, instruction, and research. For many years the library has offered computer and internet access to the campus community, as many students are without devices and broadband.

The Louisiana Board of Regents formed the Digital Inclusion Task Force during the COVID-19 pandemic to address the digital divide in higher education. I was invited to participate in the task force’s Inclusion Operational Action Team subgroup. It was a natural fit since our library already offers a laptop loaner program and hosts Digital Literacy Days, which educate our community about opportunities to improve digital skills. Other partners on the task force include librarians, educational technologists, and faculty members from other Louisiana universities.

Hertzel: In Long Beach, California, it is people of color and our older-adult population who are disproportionately affected by digital inequities. In 2021, the city reported that 10.1% of Latinx households, 11.4% of Black/African-American households, and 11.7% of Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander households lacked an internet subscription—more than twice the rate of white households (4.6%). Among adults age 65 years and older, 15.3% are without computer access.

In 2019, I joined the city’s newly formed Digital Inclusion Stakeholder Committee as a representative for Long Beach Public Library (LBPL). The committee provided guidance on developing the vision, goals, and strategies that eventually became the Digital Inclusion Roadmap. Partners include city departments, community-based organizations, digital inclusion nonprofits, funders, internet service providers, K–12 and higher education institutions, and private technology companies. Community members were also interviewed at pop-up events, and their responses were included in the road map.

How does your coalition address the three main aspects of digital equity: affordable, high-speed internet; internet-enabled devices; and digital literacy training?

Hertzel: Our committee reflects the spectrum of digital inclusion and was split into three working groups that cover capacity, connectivity, and technology. The capacity group, of which I am a part, focused discussions on leadership, multilingual computer literacy training and support, technology jobs and internship opportunities, job preparedness, and computer literacy skills development. Some of the partners in this group included the YMCA of Greater Long Beach, the Long Beach Economic Development Commission, and Gals Starting Over, a community program designed to help women restart their careers.

Kight: Our task force was charged with developing a plan to ensure that higher education faculty members have access to professional development, students have the digital literacy skills to be successful online, and students have the tools to get online, including affordable and sustainable broadband connections. To implement these goals, partnerships and collaborations have been essential. For example, LOUIS: The Louisiana Library Network, our statewide higher education consortium, provided institutions with access to training modules from Northstar Digital Literacy that were shared with students and faculty.

Kehoe: The term I tend to use is usable device instead of internet-enabled device. Smartphones are internet-enabled devices, but it is very difficult to submit a résumé or write a research paper on them. Pew Research Center data suggests that smartphone and cellphone ownership is nearly ubiquitous, but this device alone does not meet many people’s needs.

While our collaborative is open to organizations and individuals with a common interest in bridging the digital divide, it does not itself often sponsor programming. Every organization in Digital Durham is independent, but efforts are amplified by the group. For example, Durham County Library lends technology kits and Wi-Fi hotspots, and offers digital literacy classes. Members are aware of these offerings and can tell their users about them or partner with the library on a program to increase the capacity of the service. As a group, we share best practices and data, and partner on grant applications.

What successes has your digital equity coalition seen?

Kight: Task force meetings allow each campus to express its digital inclusion needs and schools are able to receive resources, such as Wi-Fi hotspots and mobile devices. While I do not know exact numbers, I can state that before the COVID-19 pandemic, the library had a long list of students—and some faculty members—who were waiting to check out laptops. The list still exists, but we’re closing the gap thanks to CARES Act funding and the task force’s efforts. The university community is now more aware of the need for digital literacy, and our administrators now champion the library’s efforts.

Hertzel: The connections made on this committee have allowed LBPL to accomplish goals that we couldn’t otherwise on our own. The Digital Inclusion Resources Hotline, for instance, was a partnership of three city departments—LBPL, the Economic Development Department, and the Technology and Innovation Department—and funded by the CARES Act.

Long Beach has a resource called ConnectedLB, where residents can enter their information on a website and find low-cost options for internet services, computers, and hotspots. But what if you don’t have internet at all? A website doesn’t help residents get connected in that situation. The committee thought, what about a multilingual hotline that people can call for help?

When the hotline was in its early stages, LBPL Manager of Branch Libraries Cathy De Leon reminded city partners that the library is perfectly positioned to staff such a service, because digital navigation is already an integral part of our day-to-day work.

Kehoe: Some highlights of Digital Durham’s work have so far included completing an inventory of resources and gaps, meeting with Detroit’s director of digital inclusion, and holding seven online focus groups and surveying 300 residents in English and Spanish online and in-person—input that was used to craft our digital equity plan.

Our partners have themselves done innovative work. Durham Public Schools was able to increase parents’ digital literacy skills by holding evening sessions that made them more aware of the digital tools their children use in class. The district’s foundation provided grant funding to cover childcare for these events. And Durham Public Library’s Stanford L. Warren branch is using a state Library Services and Technology Act grant to pilot a digital navigator program, where users can reserve appointments with librarians who personally connect them with resources over the phone or during a socially distanced session.

How has COVID-19 affected your coalition’s work?

Kight: The greatest challenge was trying to implement action plans quickly so that there wouldn’t be an interruption to services or learning. Task force members were also experiencing work-life balance challenges and needing support. I remember one meeting where the group was divided into smaller Zoom rooms to discuss a topic, and much of the time was spent talking about mental health and a need for institutions to respond in this area.

The task force advised campuses to consider the emotional needs of their communities as decisions were made concerning housing, library and technology access, assignments, and instruction. At my library, I made sure employees—including student workers—knew that counseling was available to them. When campus reopened, I worked with the counseling center’s director to reserve individual study rooms for private and confidential virtual counseling sessions for students without computers.

Hertzel: During the pandemic, LBPL launched Tech To-Go, a Chromebook and hotspot lending service, and served as a distribution point for the city’s Free Internet Services and Computing Devices Program, a partnership that has so far distributed 1,093 hotspots and 1,592 computing devices on a first-come, first-served basis to qualified, low-income residents.

Kehoe: In March 2020, our hearts were breaking over the digital inclusion work that we knew needed to be done, but our options were so limited. Digital literacy classes were canceled, and those partners who distributed low-cost devices were quickly running out of inventory. Durham Public Schools was working to get kids laptops and internet for remote schooling, and we knew telehealth was going to present a challenge for many users. Moreover, reaching people who needed services was difficult during lockdown. Our group created fliers in English and Spanish listing options for free and low-cost internet services and spots offering free Wi-Fi that could be found in Durham and the county.

On a macro level the pandemic has magnified digital inequities in this country, and we have spent less time explaining the issues and more time developing solutions. There is now more money and focus on digital inclusion at a higher level of government than I have seen before. Billions of dollars have been earmarked to be spent on digital inclusion efforts through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Emergency Broadband Benefit, and American Rescue Plan Act. At the local level, decisions are still being made about how to spend federal funds, so there are opportunities for libraries to influence how this money should be spent.

What tips do you have for libraries looking to form or join a digital equity partnership or coalition?

Kight: Realistic goals, relevant meeting agendas, a willingness to collaborate, time, passion, and good leadership are all key elements needed for a functional and sustainable task force.

Kehoe: For those looking to form a coalition, NDIA has a guidebook. Be sure to seek out support at the state and federal level and consider becoming an NDIA affiliate. Also, make it easy for the community to find you by setting up a website with contact information.

Hertzel: Your library doesn’t need to be a city department in order to engage with your city on the topic of digital inclusion. Find the organizations that would make for appropriate stakeholders and connect. Look to other communities and libraries to see how they’re approaching the work, involving the public, and getting things done.

Source of Article